B-cell lymphocytes in Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

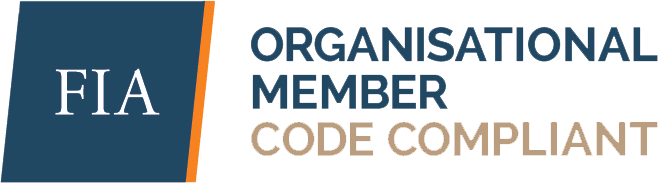

To understand DLBCL you need to know a bit about your B-Cell lymphocytes.

B-Cell lymphocytes:

- Are a type of white blood cell

- Fight infection and diseases to keep you healthy.

- Remember infections you had in the past, so if you get the same infection again, your body’s immune system can fight it more effectively and quickly.

- Are made in your bone marrow (the spongy part in the middle of your bones), but usually live in your spleen and your lymph nodes. Some live in your thymus and blood too.

- Can travel through your lymphatic system, to any part of your body to fight infection or disease.

DLBCL develops when some of your B-cells become cancerous. They grow uncontrollably, are abnormal, and do not die when they should.

When you have DLBCL your cancerous B-cell lymphocytes:

- Will not work as effectively to fight infections and disease.

- Can become larger than they should and can look different to your healthy B-cells.

- Can cause lymphoma to develop and grow in any part of your body.

- Are spread out (diffuse) rather than grouped closely together.

Although DLBCL is usually a fast growing (aggressive) lymphoma, many people with DLBCL can be cured with treatment, even if you are diagnosed with an advanced stage. An advanced stage of lymphoma is very different to advanced stages of other cancers which cannot be cured.

Causes of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

We don’t know what causes DLBCL, but different risk factors are thought to increase your risk of developing it. Some, risk factors for DLBCL are thought to include the following if you:

- Have a condition affecting your immune system such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- Are taking medicines that suppress your immune system, such as those taken after an organ transplantation.

- Have a family member with lymphoma.

- Have hepatitis C – a virus affecting your liver.

- Were overweight as a child.

*It is important to note, not all people who have these risk factors will develop DLBCL, and some people with none of those risk factors can develop DLBCL.

For an overview of DLBCL presented by haematologist Michael Dickinson please watch the below video.

Symptoms of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

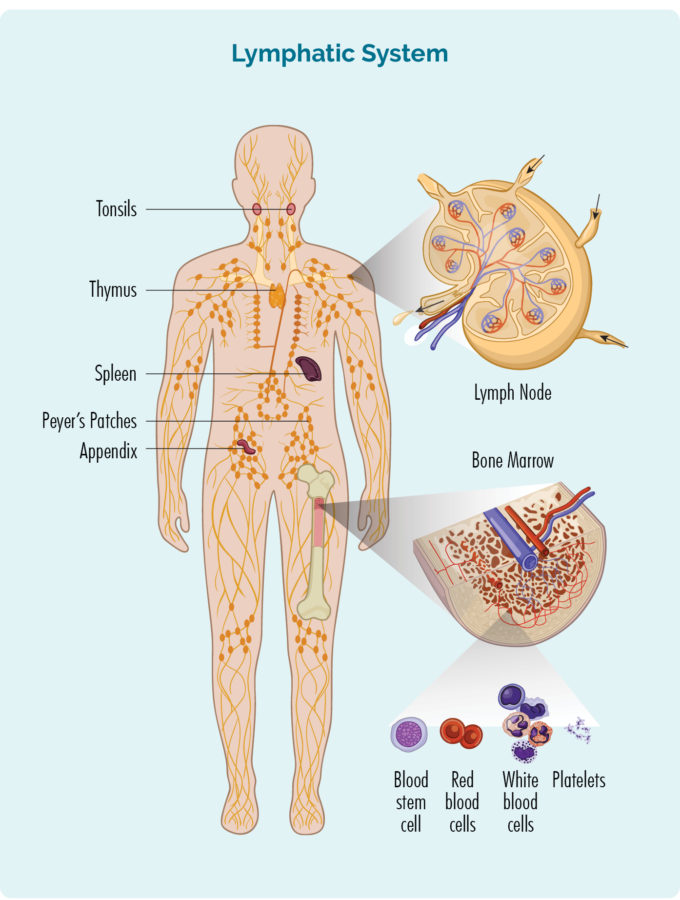

The first sign or symptom of DLBCL you get may be a lump, or several lumps that continue to grow. You might feel or see them on your neck, armpit or groin. These lumps are enlarged lymph nodes (glands), swollen by having too many cancerous B-cells growing in them.

They often start in one part of your body, and then spread throughout your lymphatic system and to other parts of your body including your:

- spleen

- thymus

- lungs

- liver

- bones

- bone marrow

- central nervous system (CNS)

- other organs

Organs of your lymphatic system – Spleen and thymus

Your spleen is an organ that filters your blood and keeps it healthy. It is also an organ of your lymphatic system where your B-cell lymphocytes live and produce antibodies to fight infection. It is on the left side of your upper abdomen under your lungs and near your stomach (tummy).

When your spleen gets too big, it can put pressure on your stomach and make you feel full, even if you haven’t eaten very much.

Your thymus is also part of your lymphatic system. It is a butterfly shaped organ that sits just behind your breast bone in the front of your chest. Some B-cells also live and pass through your thymus.

Depending on where you DLBCL is growing you may have different symptoms as listed below.

Symptoms of DLBCL (Table one)

Area affected | Symptoms |

Gut – including your stomach and bowel | Nausea with or without vomiting (feeling sick in your tummy or throwing up). Diarrhoea or constipation (watery or hard poo). Blood when you go to the toilet. Feeling full even if you haven’t eaten much. |

Central nervous system (CNS) – including your brain and spinal cord | Confusion or memory changes. Personality changes. Seizures. Weakness, numbness, burning or pins and needles in your arms and legs. |

Chest | Shortness of breath Chest pain A dry cough |

Bone marrow | Low blood counts including red cells, white cells and platelets resulting in: o Shortness of breath. o Infections that deep coming back or are difficult to get rid of. o Unusual bleeding or bruising. |

Skin | Red or purple looking rash. Lumps and bumps on your skin which may be skin coloured or red or purple. Itching. |

General symptoms of lymphoma

General symptoms of lymphoma may include:

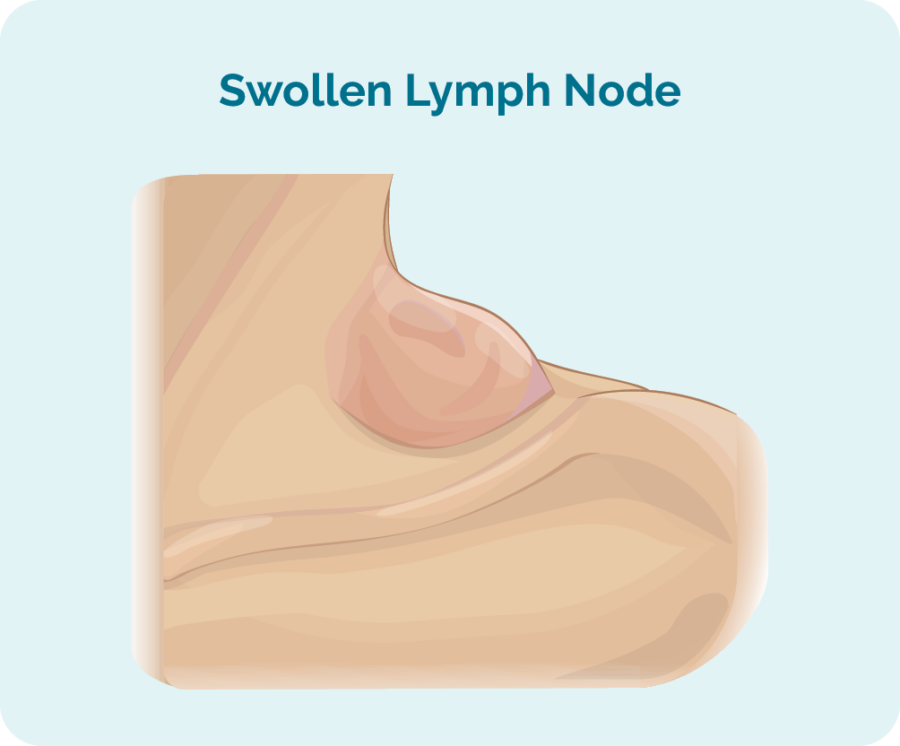

- B-symptoms – see picture below

- swollen lymph nodes (glands)

- feeling unusually tired (fatigued)

- feeling out of breath

- itchy skin

- infections that don’t go away or keep coming back

- changes to your blood tests

- low red cells and platelets

- too many lymphocytes and/or lymphocytes that do not work properly

- lowered white cells (including neutrophils)

- high lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) – a type of protein used to make energy. If your cells are damaged by your lymphoma, LDH can spill out of your cells and into your blood

- high beta-2 microglobulin – a type of protein made by lymphoma cells. It can be found in your blood, urine or cerebral spinal fluid

When to contact your doctor

You should contact your doctor if:

- you have swollen lymph nodes that do not go away, or if they are larger than you would expect for an infection

- you are often short of breath without reason

- you are more tired than usual and it does not get better with rest or sleep

- you notice unusual bleeding or bruising (including in our poo, from your nose or gums)

- you develop an unusual rash (a purple of red spotty rash can mean you have some bleeding under your skin)

- your skin is more itchy than usual

- you develop a new dry cough

- you experience B symptoms

It’s important to note that many of the signs and symptoms of DLBCL can be related to causes other than cancer. For example, swollen lymph nodes can also happen if you have an infection. Usually though, if you have an infection, the symptoms will improve and the lymph nodes will return to normal size in a few weeks.

With lymphoma, these symptoms will not go away. They may even get worse.

How is Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) diagnosed

Diagnosing DLBCL can sometimes be difficult and can take several weeks.

If your doctor thinks that you may have lymphoma, they will need to organise a number of important tests. These tests are needed to either confirm or rule out lymphoma as the cause for your symptoms. Because there are several different subtypes of DLBCL, you may have extra tests to find out which one you have. This is important because the management and treatment of your subtype may be different to other subtypes of DLBCL.

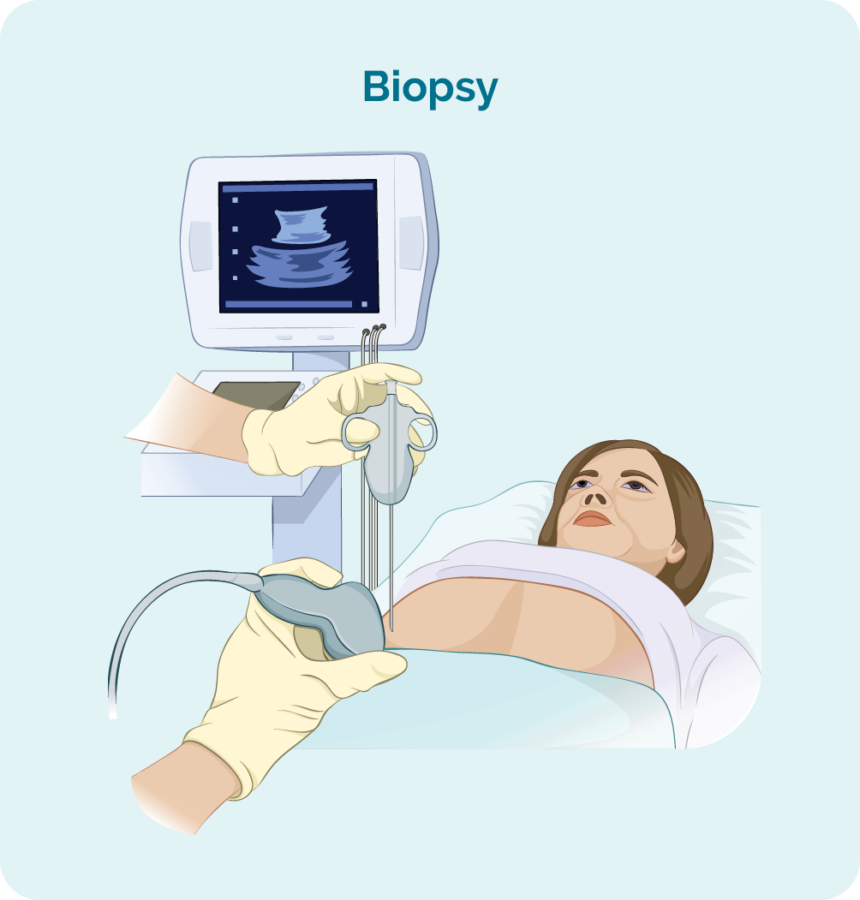

Biopsy

To diagnose DLBCL you will need a biopsy. A biopsy is a procedure to remove part, or all of an affected lymph node and/ or a bone marrow sample. The biopsy is then checked by scientists in a laboratory to see if there are changes that help the doctor diagnose DLBCL.

When you have a biopsy, you may have a local or general anaesthetic. This will depend on the type of biopsy and what part of your body it is taken from. There are different types of biopsies and you may need more than one to get the best sample.

Core or fine needle biopsy

Core or fine needle biopsies are taken to remove a sample of swollen lymph node or tumour to check for signs of DLBCL.

Your doctor will usually use a local anaesthetic to numb the area so you don’t feel any pain during the procedure, but you will be awake during this biopsy. They will then put a needle into the swollen lymph node or lump and remove a sample of tissue.

If your swollen lymph node or lump is deep inside your body the biopsy may be done with the help of ultrasound or specialised x-ray (imaging) guidance.

You might have a general anaesthetic for this (which puts you to sleep for a little while). You may also have a few stitches afterwards.

Core needle biopsies take a bigger sample than a fine needle biopsy.

Excisional node biopsy

Excisional node biopsies are done when your swollen lymph node or tumour are too deep in your body to be reached by a core or fine needle biopsy. You will have a general anaesthetic which will put you to sleep for a little while so you stay still, and feel no pain.

During this procedure, the surgeon will remove the whole lymph node or lump and send it to pathology for testing.

You will have a small wound with a few stitches, and a dressing over the top.

Stitches usually stay in for 7-10 days, but your doctor or nurse will give you instruction on how to care for the dressing, and when to return to have the stitches out.

Blood tests

Blood tests are taken when trying to diagnose your lymphoma, but also throughout your treatment to make sure your organs are working properly and can cope with our treatment.

Results

Once your doctor gets the results from you blood tests and biopsies they will be able to tell you if you have DLBCL and may also be able to tell you what subtype of DLBCL you have. They will then want to do more tests to stage and grade your DLBCL

Staging and Grading Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Once you have been diagnosed with DLBCL, your doctor will have more questions about your lymphoma. These will include:

- What stage is your lymphoma?

- What grade is your lymphoma?

- What subtype of DLBCL do you have?

Click on the headings below to learn more about staging and grading.

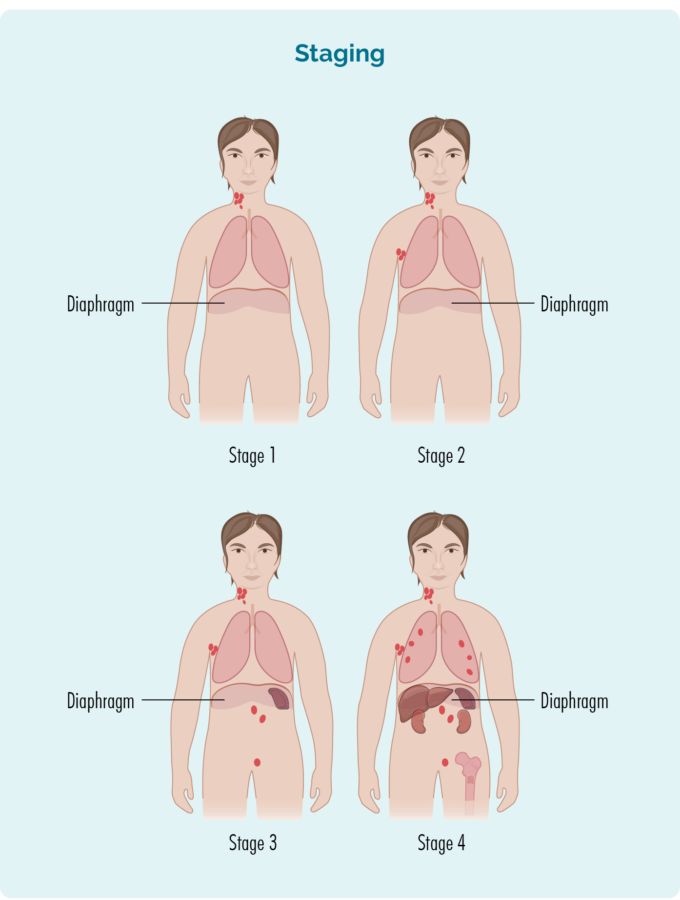

Staging refers to how much of your body is affected by your lymphoma – or how far it has spread from where it first started.

B-cells can travel to any part of your body. This means that lymphoma cells (the cancerous B-cells), can also travel to any part of your body. You will need to have more tests done to find this information. These tests are called staging tests and when you get results, you will find out if you have stage one (I), stage two (II), stage three (III) or stage four (IV) DLBCL.

Your stage of DLBCL will depend on:

- How many areas of your body have lymphoma

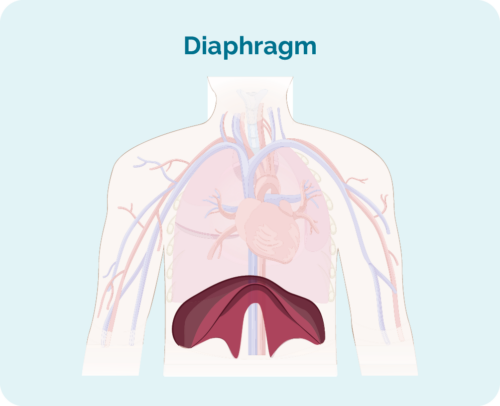

- Where the lymphoma is including if it is above, below or on both sides of your diaphragm (a large, dome-shaped muscle under your rib cage that separates your chest from your abdomen)

- Whether the lymphoma has spread to your bone marrow or other organs such as your liver, lungs, skin or bone.

Stages I and II are called ‘early or limited stage’ (involving a limited area of your body).

Stages III and IV are called ‘advanced stage’ (more widespread).

Stage 1 | One lymph node area is affected, either above or below the diaphragm*. |

Stage 2 | Two or more lymph node areas are affected on the same side of the diaphragm*. |

Stage 3 | At least one lymph node area above and at least one lymph node area below the diaphragm* are affected. |

Stage 4 | Lymphoma is in multiple lymph nodes and has spread to other parts of the body (e.g. bones, lungs, liver). |

Extra staging information

Your doctor may also talk about your stage using a letter, such as A,B, E, X or S. These letters give more information about the symptoms you have or how your body is being affected by the lymphoma. All this information helps your doctor find the best treatment plan for you.

Letter | Meaning | Importance |

A or B |

|

|

E & X |

|

|

S |

|

(Your spleen is an organ in your lymphatic system that filters and cleans your blood, and is a place your B-cells rest and make antibodies) |

Tests for staging

To find out what stage you have, you may be asked to have some of the following staging tests:

Computed tomography (CT) scan

These scans takes pictures of the inside of your chest, abdomen or pelvis. They provide detailed pictures that provide more information than a standard X-ray.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

This is a scan that takes pictures of the inside of your whole body. You will be given and needle with some medicine that cancerous cells – such as lymphoma cells absorb. The medicine that helps the PET scan identify where the lymphoma is and the size and shape by highlighting areas with lymphoma cells. These areas are sometimes called “hot”.

Lumbar puncture

A lumbar puncture is a procedure done to check if you have any lymphoma in your central nervous system (CNS), which includes your brain, spinal cord and an area around your eyes. You will need to stay very still during the procedure, so babies and children may have a general anaesthetic to put them to sleep for a little while when the procedure is done. Most adults will only need a local anaesthetic for the procedure to numb the area.

Your doctor will put a needle into your back, and take out a little bit of fluid called “cerebral spinal fluid” (CSF) from around your spinal cord. CSF is a fluid that acts a bit like a shock absorber to your CNS. It also carries different proteins and infection fighting immune cells such as lymphocytes to protect your brain and spinal cord. CSF can also help drain any extra fluid you may have in your brain or around your spinal cord to prevent swelling in those areas.

The CSF sample will then be sent to pathology and checked for any signs of lymphoma.

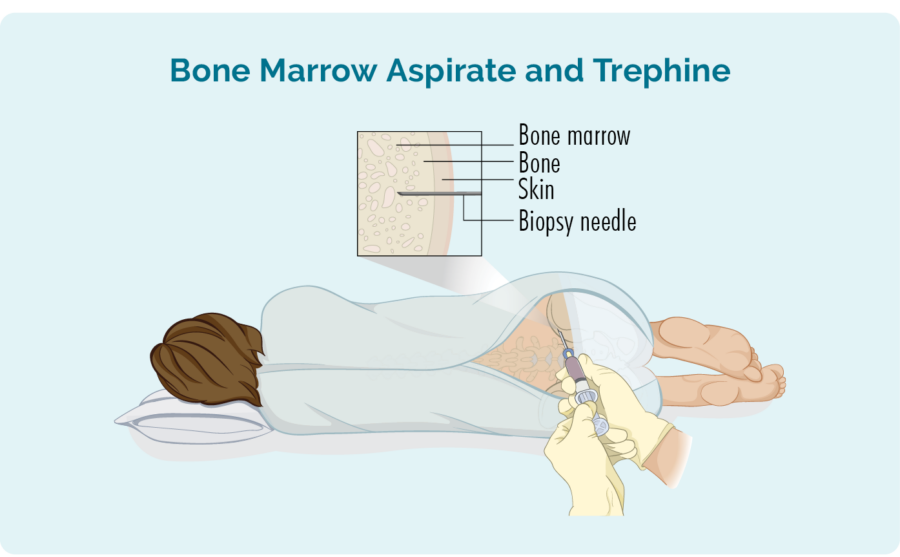

Bone marrow biopsy

- Bone marrow aspirate (BMA): this test takes a small amount of the liquid found in the bone marrow space.

- Bone marrow aspirate trephine (BMAT): this test takes a small sample of the bone marrow tissue.

The samples are then sent to pathology where they are checked for signs of lymphoma.

The process for bone marrow biopsies can differ depending on where you are having your treatment, but will usually include a local anaesthetic to numb the area.

In some hospitals, you may be given light sedation which helps you to relax and can stop you from remembering the procedure. However many people do not need this and may instead have a “green whistle” to suck on. This green whistle has a pain killing medication in it (called Penthrox or methoxyflurane), that you use as needed throughout the procedure.

Make sure you ask your doctor what is available to make you more comfortable during the procedure, and talk to them about what you think will be the best option for you.

More information on bone marrow biopsies can be found at our webpage here.

Your lymphoma cells have a different growth pattern, and look different to normal cells. The grade of your lymphoma is how quickly your lymphoma cells are growing, which affects the way look under a microscope. The grades are Grades 1-4 (low, intermediate, high). If you have a higher grade lymphoma, your lymphoma cells will look the most different from normal cells, because they are growing too quickly to develop properly. An overview of the grades is below.

- G1 – low grade – your cells look close to normal, and they grow and spread slowly.

- G2 – intermediate grade – your cells are starting to look different but some normal cells exist, and they grow and spread at a moderate rate.

- G3 – high grade – your cells look fairly different with a few normal cells, and they grow and spread faster.

- G4 – high grade – your cells look most different to normal, and they grow and spread the fastest.

All this information adds to the whole picture your doctor builds to help decide the best type of the treatment for you.

It is important that you talk to your doctor about your own risk factors so you can have clear idea of what to expect from your treatments.

Subtypes of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

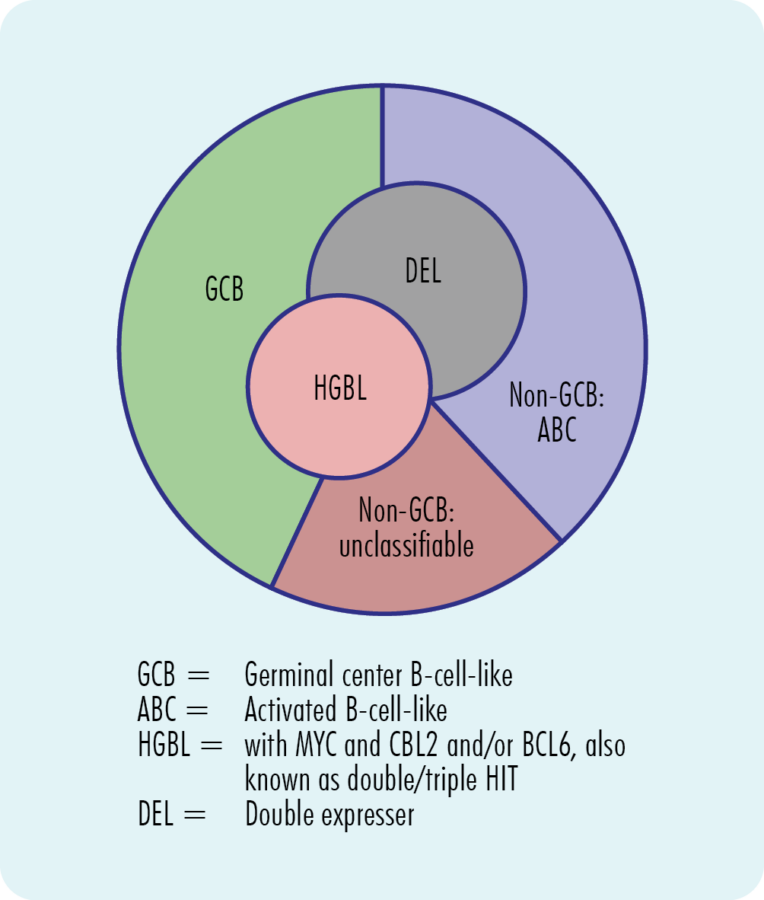

There are many subtypes of DLBCL. The two main subtypes are named based on the specific cell your lymphoma began growing from. The most common is “Activated B-cell (ABC)”, with about half of all patients with DLBCL having this subtype. The other main subtype of DLBCL is “Germinal Cell B-cell (GCB)”, with about 3 in every 10 people with DLBCL having this subtype.

Your doctor can tell whether you have the GCB or ABC subtype by looking at your lymphoma cells in pathology. The two subtypes look different by having different proteins on the surface of the cells, and different genetic mutations.

Once your doctor and treating team know if you have GCB or ABC, they may do additional cytogenetic tests on your lymphoma cells. These tests check for other genetic changes in your chromosomes and genes (called rearrangements). You can find more information on this further down this page under the heading “Understanding your lymphoma genetics”.

DLBCL can also be called nodal or extra-nodal. Nodal means that it started in your lymph nodes, whereas extra-nodal means it started outside of your lymphatic system. Some extra-nodal places that DLBCL can start include your skin, breasts, testicles, liver, lung, bone, brain, stomach or bowels.

Click on the banners below if you would like to learn more about the other subtypes of DLBCL that make up the remainder of cases.

Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) is a rare aggressive (fast-growing) type of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. It used to be classified as a sub-type of DLBCL, but has now been reclassified by the World Health Organisation as a subtype on its own.

For more information on PMBCL, please see our Primary Mediastinal B – cell lymphoma (PMBCL) webpage here, or our factsheet here.

T-cell/histiocyte rich B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL) is a rare subtype of DLBCL that can be very difficult for your doctor to diagnose. It is difficult to diagnose because it looks a lot like two other subtypes of lymphoma. For this reason, some people with T/HRBCL can get a wrong diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma or peripheral T-cell lymphoma, before getting the right diagnosis. You will need some special tests to diagnose T/HRBCL called immunohistochemistry tests. This is a special test done on your biopsies so your doctor can learn more about your lymphoma.

T-cells are another type of lymphocyte cell that helps your immune system remember infections you’ve had in the past. They help to keep your immune system in check so it doesn’t work too hard, and also supports other cells of your immune system to work more effectively. Histiocytes are also a type or immune cell called a phagocyte. Phagocytes help to protect you from infection and disease because they recognise the bad cells and eat them.

If you have T/HRBCL – you have too many T-cells and histiocytes (which is why it’s called “rich” – T/HR) while also having cancerous B-cell lymphocytes (BCL).

Standard treatment for T/HRBCL is the same as most other subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), discussed later on this webpage.

EBV-positive DLBCL not otherwise specified is a subtype of DLBCL that can occur in young people, but most commonly affects people over 50 years of age. It occurs in some people who have had a virus called Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which affects B-cells. EBV causes glandular fever (also called “mono” or the kissing disease). However, only a very small number of people who have had EBV go on to develop EBV-positive DLBCL. Unfortunately we currently have no way of knowing who will develop this lymphoma after infection with EBV.

Symptoms will depend on where your lymphoma is growing. It usually starts in your lymph nodes (called nodal lymphoma) which can cause a new lump to come up. This is usually in your neck, armpit, groin or tummy, but can be anywhere in your body.

Other places it can grow and the symptoms associated with it are similar to those listed above in table one.

Standard treatment for intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is the same as most other subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), discussed later on this webpage.

ALK-positive large B-cell lymphoma is a very rare subtype of DLBCL. It can affect people of any age and is more common in men. The lymphoma cells have a gene mutation that makes a protein on the surface of their B-Lymphocyte cells called ‘anaplastic large-cell kinase’ (ALK).

Most subtypes of DLBCL have a protein on the lymphoma cells called CD20. However, ALK positive large B-cell lymphomas do not usually have the CD20 protein. For this reason, treatment will be slightly different from other DLBCL subtypes. Although most of the medications will be the same, if you have this subtype, you will not receive a monoclonal antibody medicine called rituximab. Rituximab only works when CD20 is found on the lymphoma cells. So, if you’re wondering why you may not be getting the extra medicines other patients are getting….this may be the reason.

ALK-positive large B-cell lymphoma usually starts in your lymph nodes, so a common symptom you might experience is swollen lymph nodes.

However, it can also start in areas outside of your lymphatic system, including your:

- tongue

- nasopharynx (the area at the back of your nose and mouth)

- ovaries

- liver

- breasts

- bones

- stomach

- brain or epidural space (an area surrounding your spine)

Your symptoms will related to where the lymphoma is growing.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is a rare form of an *extra-nodal DLBCL. It mostly affects older adults between 50-70 years of age. This subtype occurs equally in both men and women. The lymphoma cells are found within the inside lining of your small blood vessels. These small blood vessels are called capillaries.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma does not usually cause enlarged lymph nodes. It may affect small blood vessels in your skin or your brain. You may have central nervous system (CNS) symptoms. Your central nervous system includes your brain and spinal cord, so the symptoms you experience may include:

- confusion

- seizures

- dizziness

- weakness

Other symptoms you may experience specific to your subtype include:

- reddened patches or lumps on your skin

- an enlarged liver and/or spleen

These symptoms are in addition to the general lymphoma symptoms listed above.

Standard treatment for intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is the same as most other subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), discussed later on this webpage.

*Extra-nodal means your lymphoma developed outside of your lymph nodes.

Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare subtype of DLBCL that is considered aggressive because it grows quickly. It is more common in people aged between 50 and 60 years of age, but can occur at any age.

If you have PCNSL your lymphoma likely started in your central nervous system, which includes your brain and spinal cord.

In more than 9 out 10 people that have PCNSL the lymphoma develops in the brain, spinal cord, eye or leptomeninges (the inner two membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord).

The most common site is in the brain.

If your lymphoma has started in other parts of your body first then at some stage has spread to the brain or spinal cord, it is referred to as ‘secondary’ CNS lymphoma (SCNSL).

Treatment and management of PCNSL is different from other subtypes of DLBCL as the standard treatments cannot reach your brain and spinal cord. You can read more about the treatments for PCNSL later in the webpage under the heading Treatments.

Cutaneous (skin) B-cell lymphoma is a rare subtype of DLBCL that develops from the B-cells in your skin. Less than 1 out of 100 people with NHL will be diagnosed with this subtype.

For you doctor to diagnose you with this subtype, the lymphoma needs to be only affecting your skin.

Because this lymphoma starts in your skin, the main symptoms you may notice include are lumps, patches or a rash anywhere on your skin.

As cutaneous B-cell lymphomas are managed differently to other DLBCL subtypes, we have dedicated a different webpage to these subtypes.

You can find more specific information about cutaneous B-cell lymphoma here.

Please note that if you have been diagnosed with another subtype of DLBCL and it has spread to your skin, you should continue to look at the information on that first subtype. If the lymphoma has spread to your skin after starting somewhere else, it is considered secondary cutaneous lymphoma. Primary and secondary cutaneous lymphomas are managed differently.

Additionally, if you have cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, this is different again.

You can find more information on cutaneous T-cell lymphoma here.

Understanding your lymphoma genetics

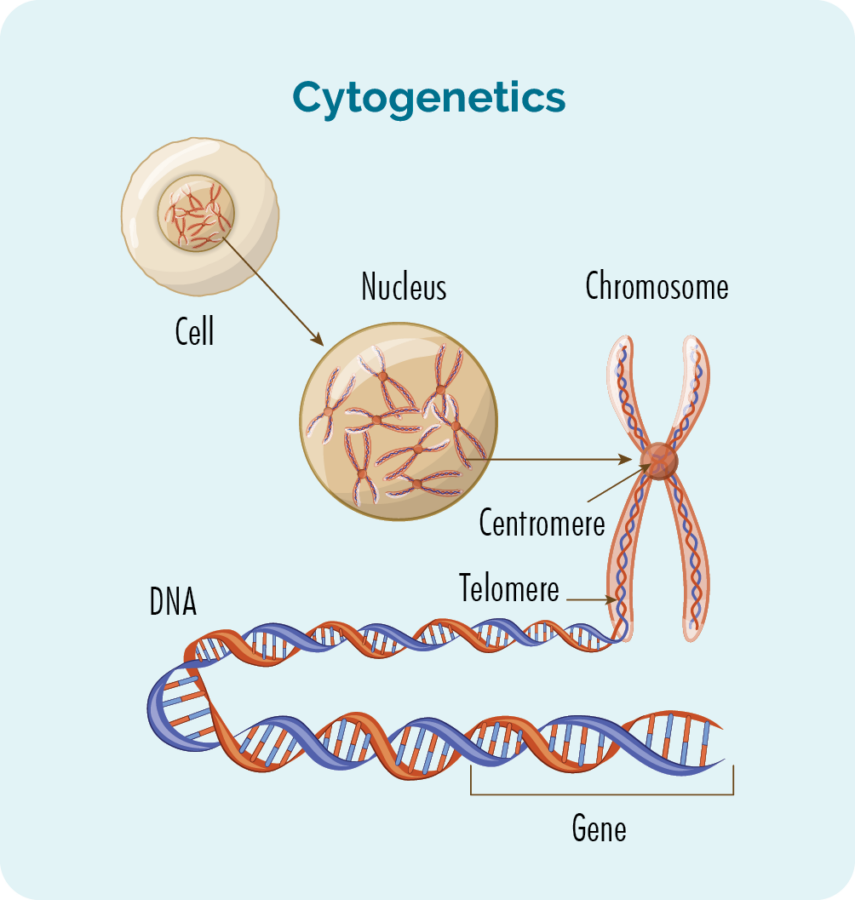

Cytogenetic tests are done to check for genetic variances that may be involved in your disease. For more information on these please see our section on understanding your lymphoma genetics further down on this page. The tests used to check for any genetic mutations are called cytogenetic tests. These tests look to see if you have any changed in chromosomes and genes.

We usually have 23 pairs of chromosomes, and they are numbered according to their size. If you have DLBCL, your chromosomes may look a little different.

What are genes and chromosomes

Each cell that makes up our body has a nucleus, and inside the nucleus are the 23 pairs of chromosomes. Each chromosome is made from long strands of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) that contain our genes. Our genes provide the code needed to make all the cells and proteins in our body, and tells them how to look or act.

If there is a change (variation) in these chromosomes or genes, your proteins and cells will not work properly.

Lymphocytes can become lymphoma cells due to genetic changes (called mutations or variations) within the cells. Your lymphoma biopsy may be looked at by a specialist pathologist to see if you have any gene mutations.

Double Hit and Triple Hit mutations in DLBCL

Some people with DLBCL may have mutations in 2 or 3 specific genes which makes the lymphoma more aggressive than DLBCL without the mutations. These mutations are called rearrangements. The genes involved always involve a gene called MYC, and a gene called BCL2 and / or BCL6.

Double Expressor

In some cases, you may not have a rearrangement in your genes, but proteins the genes control may be over expressed on your lymphoma cells. This means you have too much of the MYC or BCL proteins on your cells, which may make it a little more difficult to treat.

Rearrangement and protein expression in Double & Triple Hit, and Double Expressor Lymphomas |

||||

MYC Rearrangement |

BCL2 Rearrangement |

BCL6 Rearrangement |

Overexpression of MYC and BCL proteins |

|

Double Hit |

YES |

YES |

No |

Usually, but not always |

Triple Hit |

YES |

YES |

YES |

Usually, but not always |

Double Expressor |

No |

No |

No |

YES |

Ask your doctor to explain you individual changes and how these may impact your treatment. |

||||

Normal MYC and BCL genes help make proteins needs for your cells to grow and develop properly. If you have a rearrangement in these genes, the protein is unable to support healthy cell growth and lymphoma can develop. DLBCL with these rearrangements are called either double hit lymphoma (DHL) or triple hit lymphoma (THL). They are also sometimes called high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBL).

Testing for mutations

If you have a high-grade lymphoma your doctor may wish to do further tests on your biopsies to see if you have any genetic rearrangements or double expressing proteins. The test is called Flourescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) and looks at the different genetic markers on your biopsy samples.

However, this test is not covered by the Medicare benefits scheme so is often done at additional cost to patients, meaning you will have to pay for the tests. It can be quite expensive, and the cost can vary depending on where you get it done. Often, the treatment will not change, but in some cases it might. If the treatment would change if you had these variations, then you may consider getting the test done, or you may like to know just for interest sake.

If you choose not to have the test you will still have good care and treatment options.

Other mutations found in DLBCL

Another genetic change that can occur in DLBCL is “double expressor”. This is different to double hit DLBCL because instead of having a rearrangement of genes, the genes are in the right place but are overexpressed, meaning there are too many of the two genes.

It is also important for your doctor to know what proteins (or receptors) are on your lymphoma cells. While chemotherapy works by killing fast growing cells, other medications work by targeting a specific protein on the lymphoma cell.

So if you have particular receptors, you may receive chemotherapy and one of the targeted monoclonal antibodies. For example:

- If you have protein called CD20 on your lymphoma cells, you may receive a monoclonal antibody medication that targets CD20, such as rituximab (Mabthera or Rituxan), obinutuzumab or ofatumumab. An additional medication that targets CD20, that is only available in clinical trials is mosunetuzumab.

- If you have a protein called CD79b on your lymphoma cells you may receive a medication that targets that protein, called polatuzumab vedotin.

As you can see, understanding some of the genetics of your lymphoma is important to understand your treatment options. Please always ask your doctor to explain your results to you and how these results impact your options.

Treatment for Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

Once all of your results from the biopsy, cytogenetic testing and the staging scans have been completed, the doctor will review these to decide the best possible treatment for you. At some cancer centres, the doctor will also meet with a team of specialists to discuss the best treatment option. This is called a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

Your doctor will consider many factors about your DLBCL. Decisions on when or if you need to start and what treatment is best are based on your:

- individual stage of lymphoma, genetic changes and symptoms

- age, past medical history and general health

- current physical and mental wellbeing and patient preferences.

More tests may be ordered before you start treatment to make sure your heart, lungs and kidneys are able to cope with the treatment. These may include an ECG (electrocardiogram), lung function test or 24-hour urine collection.

Your doctor or cancer nurse can explain your treatment plan and the possible side-effects to you, and are there to answer any question you might have. It is important you ask your doctor and/or cancer nurse questions about anything you don’t understand.

You can also phone or email the Lymphoma Australia Nurse Helpline with your questions and we can help you to get the right information.

Lymphoma care nurse hotline:

Phone: 1800 953 081

Email: nurse@lymphoma.org.au

Questions to ask your doctor before you start treatment for DLBCL

It can be difficult to know what questions to ask when you are starting treatment. If you don’t know, what you don’t know, how can you know what to ask?

Having the right information can help you feel more confident and know what to expect. It can also help you plan ahead for what you may need.

We put together a list of questions you may find helpful. Of course, everyone’s situation is unique, so these questions do not cover everything, but they do give a good start.

Click on the link below to download a printable PDF of questions for your doctor.

Types of anticancer treatment for Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

There are different treatments available for Diffuse Large B cell lymphoma and they can differ depending on your specific subtype. The best treatment for you will depend on many factors including your:

- subtype of DLBCL

- stage and grade of your DLBCL

- age

- overall health

- other treatments you have, either for your DLBCL or other illnesses

- your own preference once your doctor has explained the options to you.

If you’ve had treatment for your lymphoma in the past, your doctor will consider how well it worked for you, and how bad any side-effects were for you. Your doctor will then be able to offer the best treatment options for you. If you’re not sure why the doctor has made the decisions they’ve made, please make sure to ask them to explain it to you – they are there to help you.

Some of the different types of treatments you may be offered are listed below. Click on the headings to learn more about the treatment type you are interested in.

Supportive care is given to patients and families facing serious illness. Supportive care can help patients have fewer symptoms, and actually get better faster by paying attention to those aspects of their care.

For some of you with DLBCL, your leukemic cells may grow uncontrollably and crowd your bone marrow, bloodstream, lymph nodes, liver or spleen. Because the bone marrow is crowded with DLBCL cells too young to work properly, your normal blood cells will be affected. Supportive treatment may include things like you having blood or platelet transfusions on a ward or in an intravenous infusion suite in the hospital. You may have antibiotics to prevent or treat infections.

It may involve a consultation with a specialised care team or even palliative care. It can also be having conversations about future care, which is called Advanced Care Planning. These things are part of multidisciplinary management of lymphoma.

Supportive care can include palliative care which helps to improve your symptoms and side-effects, as well as end of life care if needed

It is important to know that the Palliative Care team can be called on at any time during your treatment pathway not just at the end of life. They can help control and manage symptoms (like hard to control pain and nausea) you might be experiencing as a result of your disease or its treatment.

If you and your doctor decide to use supportive care or stop curative treatment for your lymphoma, many things can be done to help you to stay as healthy and comfortable as possible for some time.

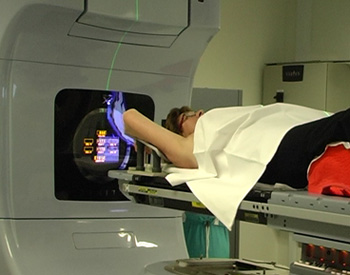

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high doses of radiation to kill lymphoma cells and shrink tumours. Before having radiation, you will have a planning session. This session is important for the radiation therapists to plan how to target the radiation to the lymphoma, and avoid damaging healthy cells. Radiation therapy usually lasts between 2-4 weeks. During this time, you will need to go to the radiation centre everyday (Monday-Friday) for treatment.

*If you live a long way from the radiation centre and need help with a place to stay during treatment, please talk to your doctor or nurse about what help is available to you. You can also contact the Cancer Council or Leukemia Foundation in your state and see if they can help with somewhere to stay.

You might have these medications as a tablet and/ or be given as a drip (infusion) into your vein (into your bloodstream) at a cancer clinic or hospital. Several different chemo medications may be combined with an immunotherapy medicine. Chemo kills fast growing cells so can also affect some of your good cells that grow fast causing side effects.

You may have a MAB infusion at a cancer clinic or hospital. MABs attach to the lymphoma cell and attract other diseases fighting white blood cells and proteins to the cancer so your own immune system can fight the DLBCL.

MABS will only work if you have specific proteins or markers on your lymphoma cells. A common marker in DLBCL is CD20. If you have this marker you may benefit from treatment with a MAB.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are a newer type of monoclonal antibody (MAB) and work a little differently to other MABS.

ICIs work when your tumour cells develop “immune checkpoints” on them which are usually only found on your healthy cells. The immuen checkpoint tells your immune system that the cell is healthy and normal, so your immune system leaves it alone.

ICIs work by blocking the immune checkpoint so your lymphoma cells can no longer pretend to be healthy, normal cells. This allows your own immune system to recognise them as cancerous, and begin an attack against them.

Chemotherapy combined with a MAB (for example, rituximab).

You may take these as a tablet or infusion into your vein. Oral therapies may be taken at home, though some will require a short hospital stay. If you have an infusion, you may have it at a day clinic or in a hospital. Targeted therapies attach to the lymphoma cell and block signals it needs to grow and produce more cells. This stops the cancer from growing and causes the lymphoma cells to die off.

A stem cell or bone marrow transplant is done to replace your diseased bone marrow with new stem cells that can grow into new healthy blood cells. Bone marrow transplants are usually only done for children with DLBCL, while stem cell transplants are done for both children adults.

In a bone marrow transplant, stem cells are removed straight from the bone marrow, where as with a stem cell transplant, the stem cells are removed from the blood.

The stem cells may be removed from a donor or collected from you after you’ve had chemotherapy.

If you the stem cells come from a donor, it is called an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

If your own stem cells are collected, it is called an autologous stem cell transplant.

Stem cells are collected through a procedure called apheresis. You (or your donor) will be connected up to an apheresis machine and your blood will be removed, the stem cells separated and collected into a bag, and then the rest of your blood is returned to you.

Before the procedure, you will get high-dose chemotherapy or full-body radiotherapy to kill off all your lymphoma cells. However this high dose treatment will also kill off all the cells in your bone marrow. So the collected stem cells will then be returned to you (transplanted). This happens in much the same was as blood transfusion is given, through a drip into your vein.

CAR T-cell therapy is a newer treatment that will only be offered if you have already had at least two other treatments for your DLBCL.

In some cases, you may be able to access CAR T-cell therapy by joining a clinical trial.

CAR T-cell therapy involves an initial procedure similar to a stem cell transplant, where your T-cell lymphocytes are removed from you blood during an apheresis procedure. Like you B-cell lymphocytes, T-cells are part of your immune system and work with your B-cells to protect you from disease and illness.

When the T-cells are removed, they are sent to a laboratory where they are re-engineered. This happens by joining the T-cell to an antigen that helps it recognise the lymphoma more clearly and fight it more effectively.

Chimeric means having parts with different origins so the joining of an antigen to the T-cell makes it chimeric.

Once the T-cells have been re-engineered they will be returned to you to start fighting the lymphoma.

First-line treatment - Starting therapy

Starting Therapy

You will need to start treatment soon after all your test results come back. In some cases, you may start before all of the results are in.

It can be quite overwhelming when you start treatment. You may have many thoughts about how you will cope, how to manage at home, or how sick you might get.

Let your treating team know if you feel you may need extra support. They may be able to help by referring you to see a social worker or other health care professional to help you work out some every day living challenges you may face. You can also reach out to the Lymphoma care nurses by clicking on the “Contact us” button at the bottom of this page.

When you do start treatment for the first time, it is called first-line therapy. You may have more than one medicine, and these may include chemotherapy, a monoclonal antibody or targeted therapy. In some cases you may have radiation treatment or surgery as well, or instead of medications.

Treatment cycles & protocols

When you have these treatments, you will have them in cycles. That means you will have the treatment, then a break, then another round (cycle) of treatment. For most people with DLBCL, chemoimmunotherapy is effective to achieve a remission (no signs of cancer).

Some genetic abnormalities may mean that targeted therapies will work best for you, and other genetic abnormalities – or normal genetics may mean chemoimmunotherapy will work best.

Some examples of chemoimmunotherapy you may get if you have DLBCL include:

R-CHOP

A standard combination of rituximab (a MAB) with chemo medicines cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and a steroid called prednisolone. Usually given on one day every 14 or 21 days. On the 4th day after treatment, you will also have an injection in your tummy to help your white blood cells grow back quicker.

R-mini-CHOP

Similar to R-CHOP above but a smaller dose. Can be used if you are elderly or your doctor is worried that you may not tolerate a full dose.

DA-R-EPOCH

A combination the same medications as R-CHOP but with the addition of another chemotherapy called etoposide. This protocol is given in different doses depending on your individual situation. The DA in the name means “dose adjusted”. It is given over a 5 day period every 21 days. On the sixth day, you will also have an injection in your tummy to help your white blood cells grow back quicker. This protocol may be given if you have:

- High grade double hit (DH), triple hit (TH) or double expressor (DEL)

- Or, if you have HIV associated lymphoma

SMARTE-R-CHOP14

Similar to R-CHOP above, but with the medication rituximab given on different days. This protocol may be offered if you are over 60 years of age, and your DLBCL cells have the marker CD20 on them.

Hyper CVAD

This protocol will usually only be offered to you if you have triple hit mutation ( a rearrangement of your MYC gene and both your BCL2 and BCL 6 genes). Hyper CVAD is given in two parts – Hyper CVAD part A and Hyper CVAD part B.

- Part A includes a steroid called dexamethasone, and chemotherapy medications cyclophosphamide twice a day for three days, doxorubicin on day four and vincristine on days 4 and 11 of the protocol. You will also have another medication called Mesna while having cyclophosphamide to help protect your bladder. On day 5, you will have an injection into your tummy called pegfilgratim to help you body create more white blood cells to protect you from infection.

- Part B includes chemotherapy called methotrexate and cytarabine. The methotrexate is given on day 1 followed by a medication called calcium folinate (leucovorin) which helps your body to get rid of excess methotrexate to prevent extreme side-effects. This will then be followed by cytarabine on days 2 and 3 and an injection of pegfilgratim on day 4

*Please note, if you have ALK positive large B-cell lymphoma, you may have similar treatments to these, but will not have the medication rituximab. This is because the lymphoma cells in ALK positive large B-cell lymphoma do not have the CD20 marker on them, which is needed for the medication to work.

- You may also be eligible to participate in a clinical trial.

Central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis (prevention)

About one in every 20 people with DLBCL can have their lymphoma come back after treatment in their CNS. It was previously thought that by giving high dose methotrexate after your first-line chemo-immunotherapy the risk of the lymphoma coming back in your CNS would be decreased.

However, studies having overwhelmingly shown that the rates of CNS disease have the same risk in those who have had the high dose methotrexate and those who have not had the high dose methotrexate. For this reason, many cancer care centers are no longer offering this treatment option, as the risks outweigh the benefits.

Second-Line treatment (After a relapse or refractory disease)

After treatment most of you will go into remission. Remission is a period of time where you have no signs of DLBCL left in your body, or when the DLBCL is under control and doesn’t require treatment. However, sometimes DLBCL can relapse (comes back) and a different treatment is given.

Few of you may not achieve remission with your first-line treatment. If this happens, your DLBCL is called “refractory”. If you have refractory DLBCL your doctor will probably want to try a different medication.

Treatment you have if you have refractory DLBCL or after a relapse is called second-line therapy. The goal of second-line treatment is to put you into remission again.

If you have further remission, then relapse and have more treatment, these next treatments are called third-line treatment, fourth-line treatment and such.

You may need several types of treatment for your DLBCL. Experts are discovering new and more effective treatments that are increasing the length of remissions. If your DLBCL does not respond well to the treatment or there is a relapse very quickly after treatment (within six months) this is known as refractory DLBCL and a different type of treatment will be needed.

Relapsed and refractory DLBCL may still be put into remission or cured with more treatment, however for a small number of people the DLBCL may be more aggressive. Ask your doctor about your own risk factors and the goal of your treatment. They will let you know if you can expect remission, cure, or what to expect if the current treatment is not effective.

How your second-line treatment is decided

At the time of relapse, the choice of treatment will depend on several factors including.

- How long you were in remission for

- Your general health and age

- What DLBCL treatment/s you have received in the past

- Your preferences.

This pattern may repeat itself over many years. New targeted therapies are now available for relapsed or refractory disease and some common treatments for relapsed DLBCL.

Common second-line treatments for DLBCL

DHAP – a common second-line chemotherapy protocol using a steroid called dexamethasone and chemotherapy medications called carboplatin and cytarabine.

ICE – this is an intense chemotherapy protocol, and includes chemotherapy medications called ifosphamide, carboplatin and etoposide. Another medication called Mesna is also given to protect your bladder.

ESHAP – this is also an intense chemotherapy protocol including a steroid called methylprednisolone and chemotherapies etoposide, cytarabine and cisplatin. This protocol may be given if you have relapsed, or if you are planning to have stem cell transplant.

GDP – This protocol may be given if you relapsed or are planning a stem cell transplant. It includes a steroid called dexamethasone and chemotherapies gemcitabine and cisplatin.

Polatuzumab vedotin – is a newer medication and is a conjugated monoclonal antibody. You may be offered this medication if you have the CD79b marker on your lymphoma cells. It is usually giev with another monoclonal antibody called rituximab (if you also have the CD20 marker on your lymphoma cells) and a chemotherapy called bendamustine. This is often used if you are not planned for stem cell transplant.

Stem cell transplant – may be offered to some people with DLBCL who have relapsed, however it is not a suitable options to everyone. You doctor will consider several things before deciding if this is good treatment option for you. These will include:

- your age

- any other illnesses (comorbidities) you may have

- how well you responded to treatments in the past.

Third-line treatment

For some people, a third or even fourth-line of treatment may be needed.

Your doctor will consider your individual circumstances when deciding on the best treatment option for you. You may be offered similar treatments to what is listed under the first and second-line treatments.

A newer option called CAR T-cell therapy has also been approved for people who have had at least two other treatments types. If you are on your third or fourth-line of treatment and you doctor has not mentioned CAR T-cell therapy we recommend you ask them about it. However, as with stem cell transplants, CAR T-cell therapy is not suitable for everyone.

Clinical trials

It is recommended that anytime you need to start new treatments you ask your doctor about clinical trials you may be eligible for.

Clinical trials are important to find new medicines, or combinations of medicines to improve treatment of DLBCL in the future.

They can also offer you a chance to try a new medicine, combination of medicines or other treatments that you would not be able to get outside of the trial. If you are interested in participating in a clinical trial, ask your doctor what clinical trials you are eligible for.

There are many treatments and new treatment combinations that are currently being tested in clinical trials around the world for patients with both newly diagnosed and relapsed DLBCL.

Prognosis for DLBCL – and what happens when treatment ends

Prognosis is the term used to describe the likely path of your disease, how it will respond to treatment and how you will do during and after treatment.

There are many factors that contribute to your prognosis and it is not possible to give an overall statement about prognosis. However, DLBCL often responds very well to treatment and many patients with this cancer can be cured – meaning after treatment, there is no sign of DLBCL in your body.

Factors that can impact prognosis

Some factors that may impact your prognosis include:

- You age and overall health at time of diagnosis.

- How you respond to treatment.

- What if any genetic mutations you have.

- The subtype of DLBCL you have.

If you would like to know more about your own prognosis, please talk with your specialist haematologist or oncologist. They will be able to explain your risk factors and prognosis to you.

Survivorship - Living with, and after cancer

A healthy lifestyle, or some positive lifestyle changes after treatment can be a great help to your recovery. There are many things you can do to help you live well with DLBCL.

Many people find that after a cancer diagnosis, or treatment, that their goals and priorities in life change. Getting to know what your ‘new normal’ is can take time and be frustrating. Expectations of your family and friends may be different to yours. You may feel isolated, fatigued or any number of different emotions that can change each day.

The main goals after treatment for your DLBCL is to get back to life and:

- be as active as possible in your work, family, and other life roles

- lessen the side effects and symptoms of the cancer and its treatment

- identify and manage any late side effects

- help keep you as independent as possible

- improve your quality of life and maintain good mental health

Different types of cancer rehabilitation may be recommended to you. This could mean any of a wide range of services such as:

- physical therapy, pain management

- nutritional and exercise planning

- emotional, career and financial counselling.